How to Read Music Fast (and Actually Enjoy It)

For many guitarists, reading music feels daunting, frustrating, and painfully slow.

Notes blur together. The eyes jump between the page and the fretboard. The brain feels overloaded trying to decode every symbol in real time. Progress feels inconsistent, and confidence suffers.

The reason reading often feels this way is simple:

Most guitarists read music one note at a time.

But music is a language — and when we learn to read it as a language, everything starts to click.

When we read written language, we don’t spell out every letter individually. We recognize words, phrases, and meaning instantly. Our eyes and brain work together to process patterns, not isolated symbols.

Music works the same way.

Why Reading Music Still Matters

Some people ask, “Why even bother learning to read music when there’s TAB, videos, and slow-motion tutorials everywhere?”

It’s a fair question.

But consider this:

Why do we put effort into learning to read written language at all?

Reading expands opportunity. It develops the mind and imagination. It builds vocabulary. It allows us to communicate ideas clearly, efficiently, and creatively. It gives us independence rather than dependence on imitation.

The same is true with music.

When you read music fluently, you gain:

🎵 Faster learning of new repertoire

🎵 Greater musical independence

🎵 Stronger rhythmic accuracy and phrasing

🎵 Better understanding of harmony and structure

🎵 Stronger musicianship overall

Reading isn’t about elitism or rules — it’s about freedom.

The Shift That Changes Everything

So how do we make reading music faster, more natural, and more enjoyable?

It starts with changing perspective.

Instead of reading individual notes as separate pieces of information, we begin recognizing musical shapes and structures.

One of the great classical guitar pedagogues, Dionisio Aguado, said:

“Guitar music is founded on chords.”

There’s deep truth in this statement. Most guitar music — whether arpeggios, melodies, or counterpoint — is built from underlying chord shapes and harmonic movement.

Once you start seeing chords rather than isolated notes, the page suddenly becomes much easier to understand.

Chunking: Seeing Music in Meaningful Groups

I call this process chunking.

Chunking means grouping individual notes into meaningful units — usually chord shapes, harmonic patterns, or familiar technical shapes on the fretboard.

Instead of reading:

note → note → note → note → panic 😅

You begin seeing:

chord shape → harmonic direction → musical gesture

This dramatically reduces cognitive load. Your brain processes fewer units of information while understanding more musical meaning.

It’s the same way we recognize words instead of spelling out every letter.

From Symbols to Sound

When you read music through chunking:

Your eyes move more confidently across the page

Your hands anticipate shapes rather than reacting to individual notes

Your memory improves

Your sight-reading becomes faster and calmer

Your interpretation becomes more musical

You’re no longer decoding — you’re reading.

This shift turns reading from a mechanical task into a musical experience.

Applying This to Real Music

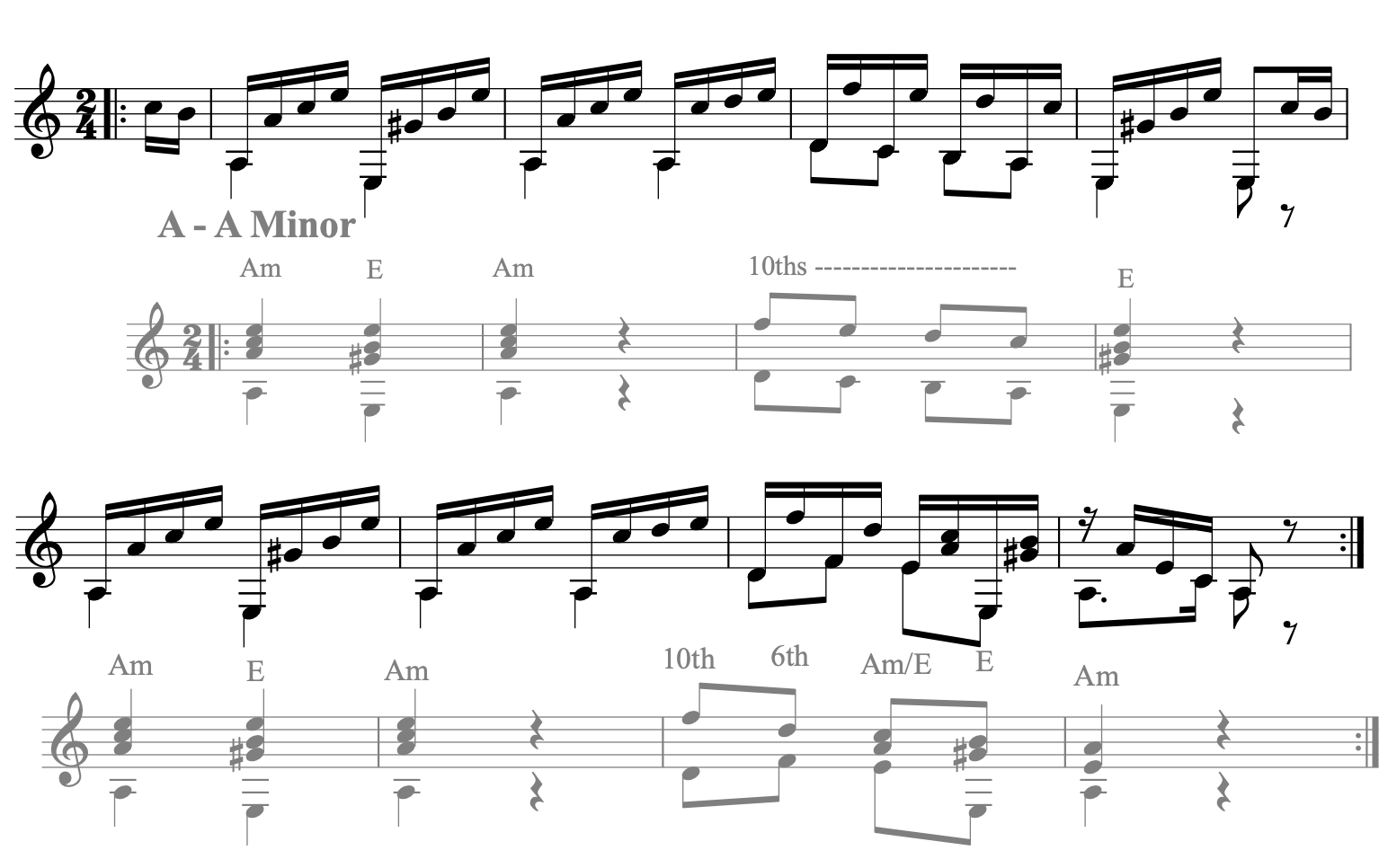

Below, you’ll see an example from a piece by Carulli, first shown exactly as written — a stream of notes that can feel intimidating at first glance.

When we apply chunking, those same notes reveal clear chord shapes and harmonic patterns that instantly simplify the reading process and guide the hands naturally on the guitar.

Once you train your eye to see these patterns, reading becomes faster, more confident, and far more enjoyable.

With all the individual notes, this can seem daunting to read

If you can ‘see’ music like the bottom stave, then you will learn to read fast. Notice that there is also a simple analysis of each chord too. This is true musical reading, where we see the words of music and understand the meaning of each note.

A Skill Worth Cultivating

Reading music fluently is not about perfection. It’s about building a healthy relationship with the score — one that supports curiosity, musical understanding, and creative growth.

Like any language, fluency develops gradually through consistent exposure, thoughtful practice, and the right mental framework.

And once it clicks, it opens an entirely new level of musical freedom.